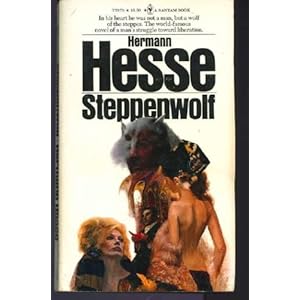

Hermann Hesse's fame has lasted,

though he is surely not quite as highly regarded as he once was.

My three dollar mass-market paperback copy of Steppenwolf, for

instance, asks and answers a question about his once massive

popularity: "Why has one European writer, Hermann Hesse,

captured the imagination and loyalty of a whole generation of

Americans? Because he is a vital spiritual force . . ." Of

course, maybe the "whole generation" phrase hints that even

the writer of the book's copy (I should note that my edition is from

some forty years after the original German publication) knew that

Hesse's fame would not stay quite so immense forever. Nowadays he is

regarded as a J.D. Salinger for a deeper crowd, the discontented

adolescent who sees phoniness everywhere but, instead of whining

humorously, turns to the things of the spirit.

Steppenwolf is maybe his best known novel, though at this

point in time, it's hard to know if that's just well-known because so

many people like the songs "Magic Carpet Ride" and "Born

to be Wild," songs by the band Steppenwolf, both still mainstays

of classic rock radio (and the latter, I just learned, the source of

the phrase "heavy metal"). Those song titles, incidentally,

seem perfectly in line with the Hesse's fascinations with man's

complicated inner nature and with the wisdom of the East. What is

fascinating is that Hesse's novel, growing out of his own history in

early twentieth century Germany, should have so much resonance the

mid-century American generation. Steppenwolf was, I read,

Timothy Leary's favorite, and one guesses that Timothy Leary was

popular among many who were reading Hesse in the 1960s and 1970s.

Showing posts with label Nobel Prize. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Nobel Prize. Show all posts

Saturday, September 3, 2011

Saturday, April 30, 2011

Heinrich Böll: AND NEVER SAID A WORD

I keep finding myself picking up these Heinrich Böll novels. This latest one, titled And Never Said a Word, was a real let-down, yet I know that I'm still going to move on to the next one. This makes me aware of the value of Böll, which lies somewhere beyond the actual qualities of his writing or his ability to come up with plots and characters. What comes through all his books, a deep moral concern and a deep moral seriousness which it gives him the ability to infuse significance into the smalles of activities, from drinking coffee to interacting with neighbors. Even when, as I suspect would happen to anyone reading this book, one gets terribly bored, one admires the man who produced it.

Tuesday, March 15, 2011

Heinrich Böll: THE LOST HONOUR OF KATHARINA BLUM

The Lost Honor is a very short novel, maybe not quite long enough to truly be a novel. At a little over a hundred rather sparsely filled pages, it meets the old Edgar Allan Poe requirement for a short story that it be able to be absorbed in a single sitting. Against Poe's recommendations, though, it doesn't aim at a single effect. Instead confronts the big ideas that motivate much of Heinrich Böll's work. In this book, as in The Clown and Billiards at Half-Past Nine, Böll sneers at the veneer of public respectability that hides immorality, shows the ways that people can use their power to manipulate others, and also betrays a general cynicism about the officialdom of postwar German society.

Tuesday, February 8, 2011

Heinrich Böll: THE CLOWN

I confess that I didn't pick up The Clown for any literary reason at all. I was interested in this book entirely because the book promised to be about a mime. It was only after that I learned anything about Heinrich Böll. The essentials on Böll are that he is a German novelist, Nobel Prize 1972, grew up in a respectable Catholic pacifist family in World War II. From this book, it seems that he has inherited his parents' distaste for war, though they also seem to have turned him against certain aspects of Catholicism and respectability.

The Clown, in spite of its title, is a rather dreary book, punctuated only rarely by moments of comedy, which sometimes come simply from the dreariness reaching such heights as to be comical.

The Clown, in spite of its title, is a rather dreary book, punctuated only rarely by moments of comedy, which sometimes come simply from the dreariness reaching such heights as to be comical.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)